A CONVERSATION WITH JHOANNA LYNN B. CRUZ

A CONVERSATION WITH JHOANNA LYNN B. CRUZ

This transpired online in January 2021.

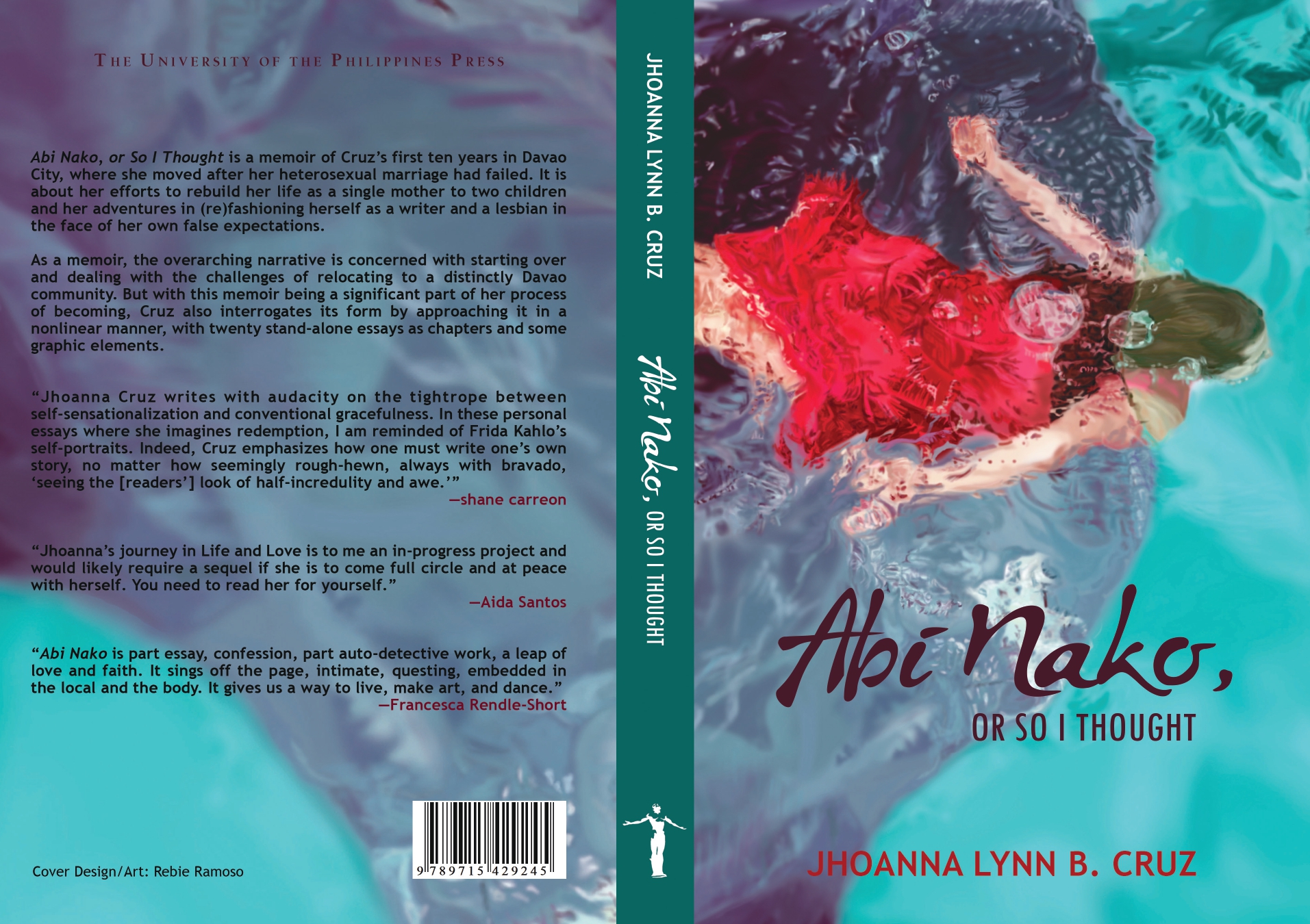

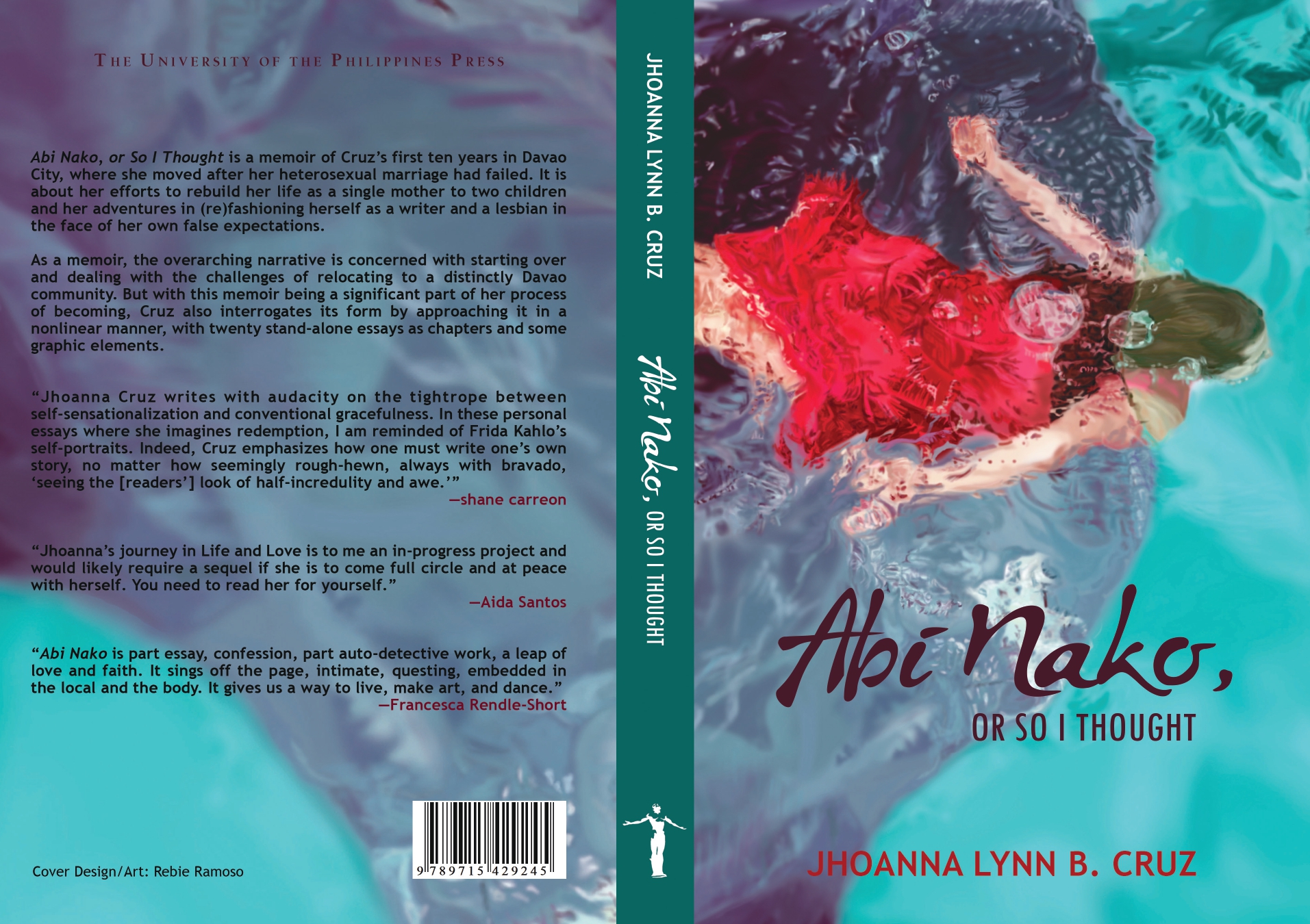

Jhoanna Lynn B. Cruz answers questions over email from Singaporean poet and Queer Southeast Asia’s co-editor, Cyril Wong, about her 2020 memoir, Abi Nako, or So I Thought, published by the University of the Philippines Press. The book encompasses in non-linear fashion her first ten years in Davao City where she had moved on from a failed heterosexual marriage, documenting efforts to rebuild and repair her life as not just a single mother, but also a lesbian writer in conflict with private ideals and expectations.

Cyril: The last time we met for real was at the 2018 George Town Literary Festival, where we both spoke on a panel about ‘Resisting White Queerness’. Since then, a pandemic has taken over the world and divided us in ways that are changing or even potentially devolving as we speak. What is it like to publish a memoir like yours in the thick of the coronavirus crisis, a modern-day plague that connects us all in painfully ironic ways? Is it still important to write about and assert (as you have) our queerness in surreally challenging and self-isolating times?

Jhoanna: As you know, we don’t stop being queer during a pandemic. In fact, I think our identity issues have become even more stark. For instance, without public events like the Pride March, how do we continue to advocate for LGBTQ+ rights on a large scale? And with lockdowns, many young queers have had to live in close quarters with families that do not accept them (or do not even know they are queer), enduring suffering without relief or refuge, which we often had with friends, our chosen family. I hope my book somehow fills that gap for queer readers to feel seen and safe. I hope my writing voice is like an elder sister to younger readers and a good friend to older ones—a companion in the journey towards healing and wholeness. Nothing sententious, just another person trying to make sense of her experiences and forgiving herself for her many failings through writing.

Cyril: You mentioned your fascination with the phrase, ‘abi nako’, in relation to moving to Davao where you had to make sense of the world through the Cebuano language (or Binisaya, colloquially). In Filipino, the phrase translates as ‘akala ko’: approximately ‘or so I thought’. You talk about owning your misconceptions and your misreadings in your book. How have such ‘misreadings’ evolved for you over time, especially after writing the memoir and since living in Davao?

Jhoanna: I hoped that my memoir would embody the ways by which my misreadings or false expectations evolved in the ten-year time frame of the narrative. Coming face-to-face with my mistakes at each turn felt like GPS reconfiguring a route—I had to keep negotiating my expectations of myself and of others as a form of survival. After I wrote the memoir and submitted it to the UP Press, my partner Mags and I broke up. And here was a book that memorialized that particular ‘abi nako’ misreading. I did consider revising it to show the actual arc of the relationship, but it would have gone beyond the timeline of the memoir. I decided to stand by the integrity of that decade, as well as that relationship, although in my epilogue I did suggest why that relationship ended. ‘Oops, I did it again!’ was the harder refrain. Yet I know I will keep doing it until I’ve finally (finally) learned what I need to learn.

Cyril: Australian novelist and your PhD supervisor, Francesca Rendle-Short described your book as ‘part essay, confession, part auto-detective work, a leap of love and faith’. I agree most with the last bit, particularly as regards your private reconciliations between the ways in which the past has defined you and how you define yourself now. What are the lingering identity-issues or insights about intimate relationships that you are still grappling with, long after the memoir is written?

Jhoanna: I think I will always be grappling with the same proverbial questions lesbian critics have asked: What is a lesbian? What is a lesbian text? That is to say, ‘Am I a lesbian?’ ‘In what ways is my writing lesbian?’ I tried to answer this in my PhD dissertation with the concept of Pagka–lesbiana. In Tagalog, the prefix pagka– denotes a state of being, but it is also used to refer to an action that has just happened and will quickly be followed by another, e.g. the adverb pagkagawa, meaning ‘after doing (something)’. Another meaning is the manner by which an action was done, e.g. pagkakagawa, meaning ‘how it was done’. Because of these other meanings, to me pagka– suggests something that is performed—not a given state. Through my practice of living and writing, I try to show how the prefix pagka– suggests a potential space for becoming or identity construction even as it literally means a state of being. It resonates with Judith Butler’s notion of ‘forms of gendering’, that is, the performativity of gender. To activate this potential, I use it with a hyphen as a signifier of that space. It is correctly used without a hyphen, as in pagkababae, meaning femaleness, pagkalalaki, maleness, pagkatao, identity—suggesting a state of being, even essence. Used with a hyphen, pagka–babae, it will be detected as a grammatical error, which can thus draw attention to the space of potential. In addition, we don’t have a word for ‘lesbian’ in any of the Philippine languages. This has been used to keep us invisible and powerless. But I believe lesbians can also appropriate that very absence to create our own specific presence/s within the Philippine culture. We generally use the term ‘lesbiana’, derived from the English, with the suffix ‘a’ to denote a female person in Tagalog. But through the dynamic construction of identity suggested by my concept of pagka–lesbiana, I can validate my sexual identity as a lesbian outside of the closed binary of butch/femme or the Filipino binary of ‘tomboy/babae’. And in writing, it can become an opportunity for me as a Philippine lesbian writer to explore what I think a lesbian text is, and more importantly, what it does.

Cyril: It’s a bizarre moment of karmic serendipity that as I was remembering something the Australian fictionist, Cate Kennedy, had said to me about my own writing, I then stumbled upon this line in your memoir, articulated by Cate herself after handing you her book as a present: ‘I’m always going to treasure the memory of you…holding an enthralled audience in the palm of your hand.’ Your memoir doesn’t shy away from the insecurities we all face as artists, despite the often facile appearances of success. You even write wryly about briefly being ‘a movie star’, while also wanting to be famous in order to earn your father’s attention. How do such insecurities define you now as a proudly queer writer and teacher?

Jhoanna: I think it’s important to acknowledge ‘impostor syndrome’ and the desperate need for recognition that accompanies it without having it define who we are. My experiences as a writer outside of the Philippines have been instrumental for me to see the value of my work outside of our little fish bowl. And Cate’s generosity was particularly life-changing during that liminal period in which I was testing whether I could survive outside of the fish bowl. So it turns out I’m an amphibian, after all!

Cyril: Married life for you was ‘full of contention, confusion, and concealment’. You also see yourself as a rebel – ‘a devil-of-a-woman carrying my horns proudly, whipping my tail around’ – who raises her only son as ‘a feminist boy’. Family life is rife with contradictions that nonetheless shape our moral consciousness and our present-day activism. You confess at one point that although you ‘write to stay alive’, you also thought that your writing would destroy your family. How do you sustain the act of writing as a force for good in both your personal life and the immediate world?

Jhoanna: I couldn’t write within the confines of my six-year heterosexual marriage, so I know what it’s like to live without writing. It can be done, but it was an inauthentic life. I know now that it is reciprocal—my writing sustains my living, in the same way that my living sustains my writing. But on the level of praxis, I have found, through my PhD regimen, that it is writing itself that sustains writing—just sitting down to write, even just one paragraph every day, as a discipline, without demanding that it be a masterpiece. Writing in and of itself: putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard), not what it can achieve, e.g. publication and career advancement. It was one of the biggest shifts in my writing practice as I completed my PhD—being able to somehow detach my writing from the context in which it arose and with which it continues to engage. It was liberating.

Cyril: Regularly in your memoir, you wrestle with meanings of words in Filipino and Binisaya: ‘In Binisaya, the word ginikanan is used to mean ‘parents’…In Filipino, the word is magulang…one who has…the wisdom of age. On the other hand, ginikanan comes from…gikan, which means “from.” Thus, one’s parents are literally “where one came from.” It makes me uncomfortable…Am I really their ginikanan? Are my children my fruits? Should I be congratulated for their achievements? Or blamed for their failings?’ How do we stop being defined by the languages we inhabit, or which inhabit us – is one of the urgent questions implicit throughout your writing. Has your memoir helped in clarifying this matter of linguistic conditioning?

Jhoanna: Speakers of Binisaya as a first language wouldn’t ordinarily note these phonetic and semantic details, but because I am a migrant learning a new language, I am attuned to them. I have three Philippine languages caroming inside my head, which are then translated into English in my creative writing, thus expanding the target language. My first language is Tagalog, spoken in Manila where I was born. It is the basis of the national language called ‘Filipino’. Having lived in Baguio City for six years, I have had to learn the lingua franca, Ilocano. And then moving to Davao City, I have learned Binisaya. Most Filipinos would speak their first language, plus Filipino, and English. And often, those from Tagalog-speaking areas like the National Capital Region and Luzon would not know other regional languages. The Philippines has over a hundred living languages. I like to think that I find myself in translation, thus somehow overcoming the linguistic conditioning of my first language. As Quebecois writer Nicole Brossard puts it, ‘if language was an obstacle, it was also the place where everything happens, where everything is possible’.

Cyril: ‘Dear Joy, Erased, with Thanks’ is a chapter in the shape of a poem separated by lacunae bursting with ecstatic longing – at least this is how I read it. Also, the chapter ‘The House on Macopa Street’ conveys more than the sum of its lines as a concrete-collage poem. How did you come to format and structure your memoir – and why not more chapters that burst the parameters of conventional prose?

Jhoanna: In ‘Dear Joy, Erased, with Thanks,’ I erased the last letter my abusive writer-boyfriend sent to me and it allowed me to find my essay within it: my piece, as in what I had to say about the matter, and my peace, by erasing the abusive narrative in a letter meant to deal a death-blow to me, and thus asserting my own narrative over it. I wanted to erase my ex-boyfriend’s version of me and thus give power to my version. It was both liberating to erase him, make him disappear, to release me from the stranglehold of his narrative and see my truth revealed in his own words. By erasing him, I reposition the male voice in the narrative, privileging mine. My longing lesbian voice travelled freely in the spaces between the words remaining.

The cut-up strips in the house collage signify the various displacements I have experienced while living in Davao as a migrant: losing my marriage, losing my old homes, separating from family, having to learn a new language, the break-ups and the deaths. These parts signify how I have broken up my narrative of selfhood; the self is no longer whole. In fact, the house is an illusion. I was trying to break out of the tyranny of the Gestalt. These pieces are some of my efforts to utilise what I call ‘non-linguistic tools for lesbian-essaying’, as a method for demonstrating ‘pagka-lesbiana’ in writing. Writing in English as a second language often fails me, but it doesn’t mean that my first language, Filipino, will succeed. I may speak it, but I don’t use it as a medium for my creative writing. These are times when I wish I could draw. And that impulse is fulfilled by the graphic interventions I have begun to explore in my current writing. The theoretical background is based on the work of Nicole Brossard, who asserts, ‘To write in lesbian (sic)…involves putting words on pages that evoke the voice and corporeal presence of a woman…whose passions carry her toward another woman and other women’. Brossard expresses this em–bodied desire through ‘textual in(ter)ventions’ in the ‘lexicon, with syntax, grammar, and graphesis’. She calls this strategy ‘Picture Theory’, in which ‘time and space merge so that thought itself is spatialized’ and thus ‘reality can be intercepted’ (311). This interception of reality can be expressed through the notion of ‘pagka-’, a challenge that can be approached in different ways by different lesbian writers.

Why not more pieces like this in the memoir? When I began the book project, I was still in my old mode of writing nonfiction according to the ways I was taught to write it, but in my creative practice research, I posed a challenge to myself around em-bodying my lesbian subjectivity in my writing. At the start of my PhD, I realised I didn’t want to keep doing what I had been doing in the past twenty-five years. As a creative writer, I wanted to be seen—which I thought meant I needed to write distinctly, e.g. in terms of form. I wanted to write nonfiction in my own unique voice. But I didn’t know how. I didn’t even know if I had one because up to that point, I had only been following the writing standards set by the Philippine literary system, which I had learned through the national writers workshop circuit and my Master of Fine Arts in creative writing.

These less conventional pieces are part of the output of that practice research, and suggest future directions for my writing. I want the book to demonstrate the evolution of my writing from the more conventional ‘creative nonfiction’ techniques essay ‘Sapay Koma,’ (the first essay I wrote when I moved to Davao in 2007) to more daring forays. I knew this may make the book seem uneven to some readers, but that is a risk I was willing to take in achieving this particular objective—a memoir of writing itself, not just of my living.

Cyril: One of the most moving parts of your memoir is about diving and the partner who took you along ‘on every underwater adventure…To face the possible loss of my dive buddy every time is as much a reminder of all that we have as any legal contract denied us because we are a lesbian couple.’ Maybe this isn’t a question but an acknowledgement of the power of queer love. Being queer teaches us from the get-go that what we have is already contingent and fleeting; it teaches us the value of love in ways that heteronormative people do not readily appreciate. Do you agree?

Jhoanna: Yes! But it’s really exhausting to have to keep fighting for our love, seeing it necessarily as part of a greater advocacy. Some days I just want to relax and be ‘normal,’ whatever that means; not to have to swim against the current. In diving, when the currents are too strong, advanced divers can do a ‘drift dive’, where they just let the current take them where it will. But as it is, I feel like I always have to be careful that my lesbian relationships are seen as ‘representative’ of a community that faces constant discrimination. For instance, because I’ve had relationships with men, I feel the pressure of proving (to myself and the public) that relationships with women are better. Most days they are. But some days they aren’t. Elsewhere, I’ve written an essay about violence in lesbian relationships, and part of me still feels guilty about writing and publishing it, as if I had betrayed the lesbian community.

Cyril: Personally, I see no betrayal whatsoever. From writing for or against the grain of your lesbian community, you also discuss spiritual matters as contextualised by culture, like how in the precolonial Ilocano belief system, every person has four souls, but the people of Davao do not have a similar practice. How has your sense of spirituality been transformed since living in Davao, and what is the relationship between spirituality and queerness for you today?

Jhoanna: As I wrote in the book, I left the Catholic Church because a priest had condemned me to living in sin forever unless I got my marriage legally annulled, something I do not want to do because it would affect the legitimacy of our children. (We don’t have a divorce law in the Philippines.) But what has greatly transformed my spirituality is not living in Davao per se, but becoming a pranic healer here. Learning how to use energy to heal has shown me what power I have in my own hands, through the Divine. And this divine energy does not discriminate against me based on my failed marriage or my queerness. It has taught me that I am not my body, that I am a soul, and that the soul does not have gender issues. And neither does God.

Cyril: In your startling last chapter, drawn in the form of a medical directive or legal document, you write: ‘I once identified my partner as this person who will have authority over my mortal remains. I see now that the document necessarily prioritizes my next of kin because of Philippine law.’ This is the tragedy of queer relationships as legally constrained, even condemned. Do you see any proverbial light at the end of the tunnel, or will queer people in our part of the world continue to fend for ourselves in our usual survivalist ways?

Jhoanna: Sadly, as far as Philippine law is concerned, we’re on our own. The LGBTQ+ community and its allies have been fighting to pass an anti-discrimination bill for 20 years. The only progress-of-a-kind we have seen is that the current version of the bill is now called the ‘SOGIESC-based Anti-Discrimination Act’. It shines a light specifically on ‘prohibiting discrimination, marginalization, and violence committed on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics.’ There is no mention of civil union or same-sex marriage in the bill. And as usual, it faces great opposition. I still hope it becomes a law in my lifetime. Meanwhile, we just have to keep fighting one battle at a time on the ground (or on the page), and hopefully, winning a little on our way.

* *

This transpired online in January 2021.

Jhoanna Lynn B. Cruz answers questions over email from Singaporean poet and Queer Southeast Asia’s co-editor, Cyril Wong, about her 2020 memoir, Abi Nako, or So I Thought, published by the University of the Philippines Press. The book encompasses in non-linear fashion her first ten years in Davao City where she had moved on from a failed heterosexual marriage, documenting efforts to rebuild and repair her life as not just a single mother, but also a lesbian writer in conflict with private ideals and expectations.

Cyril: The last time we met for real was at the 2018 George Town Literary Festival, where we both spoke on a panel about ‘Resisting White Queerness’. Since then, a pandemic has taken over the world and divided us in ways that are changing or even potentially devolving as we speak. What is it like to publish a memoir like yours in the thick of the coronavirus crisis, a modern-day plague that connects us all in painfully ironic ways? Is it still important to write about and assert (as you have) our queerness in surreally challenging and self-isolating times?

Jhoanna: As you know, we don’t stop being queer during a pandemic. In fact, I think our identity issues have become even more stark. For instance, without public events like the Pride March, how do we continue to advocate for LGBTQ+ rights on a large scale? And with lockdowns, many young queers have had to live in close quarters with families that do not accept them (or do not even know they are queer), enduring suffering without relief or refuge, which we often had with friends, our chosen family. I hope my book somehow fills that gap for queer readers to feel seen and safe. I hope my writing voice is like an elder sister to younger readers and a good friend to older ones—a companion in the journey towards healing and wholeness. Nothing sententious, just another person trying to make sense of her experiences and forgiving herself for her many failings through writing.

Cyril: You mentioned your fascination with the phrase, ‘abi nako’, in relation to moving to Davao where you had to make sense of the world through the Cebuano language (or Binisaya, colloquially). In Filipino, the phrase translates as ‘akala ko’: approximately ‘or so I thought’. You talk about owning your misconceptions and your misreadings in your book. How have such ‘misreadings’ evolved for you over time, especially after writing the memoir and since living in Davao?

Jhoanna: I hoped that my memoir would embody the ways by which my misreadings or false expectations evolved in the ten-year time frame of the narrative. Coming face-to-face with my mistakes at each turn felt like GPS reconfiguring a route—I had to keep negotiating my expectations of myself and of others as a form of survival. After I wrote the memoir and submitted it to the UP Press, my partner Mags and I broke up. And here was a book that memorialized that particular ‘abi nako’ misreading. I did consider revising it to show the actual arc of the relationship, but it would have gone beyond the timeline of the memoir. I decided to stand by the integrity of that decade, as well as that relationship, although in my epilogue I did suggest why that relationship ended. ‘Oops, I did it again!’ was the harder refrain. Yet I know I will keep doing it until I’ve finally (finally) learned what I need to learn.

Cyril: Australian novelist and your PhD supervisor, Francesca Rendle-Short described your book as ‘part essay, confession, part auto-detective work, a leap of love and faith’. I agree most with the last bit, particularly as regards your private reconciliations between the ways in which the past has defined you and how you define yourself now. What are the lingering identity-issues or insights about intimate relationships that you are still grappling with, long after the memoir is written?

Jhoanna: I think I will always be grappling with the same proverbial questions lesbian critics have asked: What is a lesbian? What is a lesbian text? That is to say, ‘Am I a lesbian?’ ‘In what ways is my writing lesbian?’ I tried to answer this in my PhD dissertation with the concept of Pagka–lesbiana. In Tagalog, the prefix pagka– denotes a state of being, but it is also used to refer to an action that has just happened and will quickly be followed by another, e.g. the adverb pagkagawa, meaning ‘after doing (something)’. Another meaning is the manner by which an action was done, e.g. pagkakagawa, meaning ‘how it was done’. Because of these other meanings, to me pagka– suggests something that is performed—not a given state. Through my practice of living and writing, I try to show how the prefix pagka– suggests a potential space for becoming or identity construction even as it literally means a state of being. It resonates with Judith Butler’s notion of ‘forms of gendering’, that is, the performativity of gender. To activate this potential, I use it with a hyphen as a signifier of that space. It is correctly used without a hyphen, as in pagkababae, meaning femaleness, pagkalalaki, maleness, pagkatao, identity—suggesting a state of being, even essence. Used with a hyphen, pagka–babae, it will be detected as a grammatical error, which can thus draw attention to the space of potential. In addition, we don’t have a word for ‘lesbian’ in any of the Philippine languages. This has been used to keep us invisible and powerless. But I believe lesbians can also appropriate that very absence to create our own specific presence/s within the Philippine culture. We generally use the term ‘lesbiana’, derived from the English, with the suffix ‘a’ to denote a female person in Tagalog. But through the dynamic construction of identity suggested by my concept of pagka–lesbiana, I can validate my sexual identity as a lesbian outside of the closed binary of butch/femme or the Filipino binary of ‘tomboy/babae’. And in writing, it can become an opportunity for me as a Philippine lesbian writer to explore what I think a lesbian text is, and more importantly, what it does.

Cyril: It’s a bizarre moment of karmic serendipity that as I was remembering something the Australian fictionist, Cate Kennedy, had said to me about my own writing, I then stumbled upon this line in your memoir, articulated by Cate herself after handing you her book as a present: ‘I’m always going to treasure the memory of you…holding an enthralled audience in the palm of your hand.’ Your memoir doesn’t shy away from the insecurities we all face as artists, despite the often facile appearances of success. You even write wryly about briefly being ‘a movie star’, while also wanting to be famous in order to earn your father’s attention. How do such insecurities define you now as a proudly queer writer and teacher?

Jhoanna: I think it’s important to acknowledge ‘impostor syndrome’ and the desperate need for recognition that accompanies it without having it define who we are. My experiences as a writer outside of the Philippines have been instrumental for me to see the value of my work outside of our little fish bowl. And Cate’s generosity was particularly life-changing during that liminal period in which I was testing whether I could survive outside of the fish bowl. So it turns out I’m an amphibian, after all!

Cyril: Married life for you was ‘full of contention, confusion, and concealment’. You also see yourself as a rebel – ‘a devil-of-a-woman carrying my horns proudly, whipping my tail around’ – who raises her only son as ‘a feminist boy’. Family life is rife with contradictions that nonetheless shape our moral consciousness and our present-day activism. You confess at one point that although you ‘write to stay alive’, you also thought that your writing would destroy your family. How do you sustain the act of writing as a force for good in both your personal life and the immediate world?

Jhoanna: I couldn’t write within the confines of my six-year heterosexual marriage, so I know what it’s like to live without writing. It can be done, but it was an inauthentic life. I know now that it is reciprocal—my writing sustains my living, in the same way that my living sustains my writing. But on the level of praxis, I have found, through my PhD regimen, that it is writing itself that sustains writing—just sitting down to write, even just one paragraph every day, as a discipline, without demanding that it be a masterpiece. Writing in and of itself: putting pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard), not what it can achieve, e.g. publication and career advancement. It was one of the biggest shifts in my writing practice as I completed my PhD—being able to somehow detach my writing from the context in which it arose and with which it continues to engage. It was liberating.

Cyril: Regularly in your memoir, you wrestle with meanings of words in Filipino and Binisaya: ‘In Binisaya, the word ginikanan is used to mean ‘parents’…In Filipino, the word is magulang…one who has…the wisdom of age. On the other hand, ginikanan comes from…gikan, which means “from.” Thus, one’s parents are literally “where one came from.” It makes me uncomfortable…Am I really their ginikanan? Are my children my fruits? Should I be congratulated for their achievements? Or blamed for their failings?’ How do we stop being defined by the languages we inhabit, or which inhabit us – is one of the urgent questions implicit throughout your writing. Has your memoir helped in clarifying this matter of linguistic conditioning?

Jhoanna: Speakers of Binisaya as a first language wouldn’t ordinarily note these phonetic and semantic details, but because I am a migrant learning a new language, I am attuned to them. I have three Philippine languages caroming inside my head, which are then translated into English in my creative writing, thus expanding the target language. My first language is Tagalog, spoken in Manila where I was born. It is the basis of the national language called ‘Filipino’. Having lived in Baguio City for six years, I have had to learn the lingua franca, Ilocano. And then moving to Davao City, I have learned Binisaya. Most Filipinos would speak their first language, plus Filipino, and English. And often, those from Tagalog-speaking areas like the National Capital Region and Luzon would not know other regional languages. The Philippines has over a hundred living languages. I like to think that I find myself in translation, thus somehow overcoming the linguistic conditioning of my first language. As Quebecois writer Nicole Brossard puts it, ‘if language was an obstacle, it was also the place where everything happens, where everything is possible’.

Cyril: ‘Dear Joy, Erased, with Thanks’ is a chapter in the shape of a poem separated by lacunae bursting with ecstatic longing – at least this is how I read it. Also, the chapter ‘The House on Macopa Street’ conveys more than the sum of its lines as a concrete-collage poem. How did you come to format and structure your memoir – and why not more chapters that burst the parameters of conventional prose?

Jhoanna: In ‘Dear Joy, Erased, with Thanks,’ I erased the last letter my abusive writer-boyfriend sent to me and it allowed me to find my essay within it: my piece, as in what I had to say about the matter, and my peace, by erasing the abusive narrative in a letter meant to deal a death-blow to me, and thus asserting my own narrative over it. I wanted to erase my ex-boyfriend’s version of me and thus give power to my version. It was both liberating to erase him, make him disappear, to release me from the stranglehold of his narrative and see my truth revealed in his own words. By erasing him, I reposition the male voice in the narrative, privileging mine. My longing lesbian voice travelled freely in the spaces between the words remaining.

The cut-up strips in the house collage signify the various displacements I have experienced while living in Davao as a migrant: losing my marriage, losing my old homes, separating from family, having to learn a new language, the break-ups and the deaths. These parts signify how I have broken up my narrative of selfhood; the self is no longer whole. In fact, the house is an illusion. I was trying to break out of the tyranny of the Gestalt. These pieces are some of my efforts to utilise what I call ‘non-linguistic tools for lesbian-essaying’, as a method for demonstrating ‘pagka-lesbiana’ in writing. Writing in English as a second language often fails me, but it doesn’t mean that my first language, Filipino, will succeed. I may speak it, but I don’t use it as a medium for my creative writing. These are times when I wish I could draw. And that impulse is fulfilled by the graphic interventions I have begun to explore in my current writing. The theoretical background is based on the work of Nicole Brossard, who asserts, ‘To write in lesbian (sic)…involves putting words on pages that evoke the voice and corporeal presence of a woman…whose passions carry her toward another woman and other women’. Brossard expresses this em–bodied desire through ‘textual in(ter)ventions’ in the ‘lexicon, with syntax, grammar, and graphesis’. She calls this strategy ‘Picture Theory’, in which ‘time and space merge so that thought itself is spatialized’ and thus ‘reality can be intercepted’ (311). This interception of reality can be expressed through the notion of ‘pagka-’, a challenge that can be approached in different ways by different lesbian writers.

Why not more pieces like this in the memoir? When I began the book project, I was still in my old mode of writing nonfiction according to the ways I was taught to write it, but in my creative practice research, I posed a challenge to myself around em-bodying my lesbian subjectivity in my writing. At the start of my PhD, I realised I didn’t want to keep doing what I had been doing in the past twenty-five years. As a creative writer, I wanted to be seen—which I thought meant I needed to write distinctly, e.g. in terms of form. I wanted to write nonfiction in my own unique voice. But I didn’t know how. I didn’t even know if I had one because up to that point, I had only been following the writing standards set by the Philippine literary system, which I had learned through the national writers workshop circuit and my Master of Fine Arts in creative writing.

These less conventional pieces are part of the output of that practice research, and suggest future directions for my writing. I want the book to demonstrate the evolution of my writing from the more conventional ‘creative nonfiction’ techniques essay ‘Sapay Koma,’ (the first essay I wrote when I moved to Davao in 2007) to more daring forays. I knew this may make the book seem uneven to some readers, but that is a risk I was willing to take in achieving this particular objective—a memoir of writing itself, not just of my living.

Cyril: One of the most moving parts of your memoir is about diving and the partner who took you along ‘on every underwater adventure…To face the possible loss of my dive buddy every time is as much a reminder of all that we have as any legal contract denied us because we are a lesbian couple.’ Maybe this isn’t a question but an acknowledgement of the power of queer love. Being queer teaches us from the get-go that what we have is already contingent and fleeting; it teaches us the value of love in ways that heteronormative people do not readily appreciate. Do you agree?

Jhoanna: Yes! But it’s really exhausting to have to keep fighting for our love, seeing it necessarily as part of a greater advocacy. Some days I just want to relax and be ‘normal,’ whatever that means; not to have to swim against the current. In diving, when the currents are too strong, advanced divers can do a ‘drift dive’, where they just let the current take them where it will. But as it is, I feel like I always have to be careful that my lesbian relationships are seen as ‘representative’ of a community that faces constant discrimination. For instance, because I’ve had relationships with men, I feel the pressure of proving (to myself and the public) that relationships with women are better. Most days they are. But some days they aren’t. Elsewhere, I’ve written an essay about violence in lesbian relationships, and part of me still feels guilty about writing and publishing it, as if I had betrayed the lesbian community.

Cyril: Personally, I see no betrayal whatsoever. From writing for or against the grain of your lesbian community, you also discuss spiritual matters as contextualised by culture, like how in the precolonial Ilocano belief system, every person has four souls, but the people of Davao do not have a similar practice. How has your sense of spirituality been transformed since living in Davao, and what is the relationship between spirituality and queerness for you today?

Jhoanna: As I wrote in the book, I left the Catholic Church because a priest had condemned me to living in sin forever unless I got my marriage legally annulled, something I do not want to do because it would affect the legitimacy of our children. (We don’t have a divorce law in the Philippines.) But what has greatly transformed my spirituality is not living in Davao per se, but becoming a pranic healer here. Learning how to use energy to heal has shown me what power I have in my own hands, through the Divine. And this divine energy does not discriminate against me based on my failed marriage or my queerness. It has taught me that I am not my body, that I am a soul, and that the soul does not have gender issues. And neither does God.

Cyril: In your startling last chapter, drawn in the form of a medical directive or legal document, you write: ‘I once identified my partner as this person who will have authority over my mortal remains. I see now that the document necessarily prioritizes my next of kin because of Philippine law.’ This is the tragedy of queer relationships as legally constrained, even condemned. Do you see any proverbial light at the end of the tunnel, or will queer people in our part of the world continue to fend for ourselves in our usual survivalist ways?

Jhoanna: Sadly, as far as Philippine law is concerned, we’re on our own. The LGBTQ+ community and its allies have been fighting to pass an anti-discrimination bill for 20 years. The only progress-of-a-kind we have seen is that the current version of the bill is now called the ‘SOGIESC-based Anti-Discrimination Act’. It shines a light specifically on ‘prohibiting discrimination, marginalization, and violence committed on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics.’ There is no mention of civil union or same-sex marriage in the bill. And as usual, it faces great opposition. I still hope it becomes a law in my lifetime. Meanwhile, we just have to keep fighting one battle at a time on the ground (or on the page), and hopefully, winning a little on our way.

* *

Jhoanna Lynn B. Cruz is Associate Professor at the University of the Philippines Mindanao where she teaches literature and creative writing. Her first book, Women Loving: Stories and a Play (2010), was the first sole-author anthology of lesbian-themed stories in the Philippines. She completed both a master of arts in language and literature, as well as a master of fine arts in creative writing, at De La Salle University-Manila. She holds a PhD from RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. Her latest book is a memoir Abi Nako, or So I Thought published by the University of the Philippines Press in 2020.